First, let me show you what this 1957 owner’s manual has to say about tire inflation:

Okay, let’s see here: under-inflated tires are bad, could cause blowouts, okay, got it, and of course proper inflation is great, good everything, better mileage, gets you a place among The Elect, I get it, and now overinflation, lets’s see, poor traction, blah blah blah, and wait. Bruises? Fabric breaks? Bruises? What, exactly, is Chevy saying here? Will GM send goons to work you over if your tires are overinflated? Or is this just a reminder that cars of the 1950s were full of hard, unforgiving surfaces and pointy, jabby things that would smack painfully into your tender flesh as you bounced down the road on tires as tight as snare drums, skittering all over the vast expanses of vinyl bench seat until you impacted, hard, into a chrome gargoyle installed on the dash? Honestly, this is the first time I’ve ever seen a warning for bruises in a car owner’s manual. There’s more interesting details, too! Like this–look at the bold safety hint:

See that? What’s interesting about that is that it’s sort of predicting the coming of hazard lights about a decade before they were required on cars (that would be 1968, though they had been developed earlier). The use case described here–having a flashing light on while changing a flat–is precisely the sort of thing hazard lights were designed to do. What else do we have here? Oh, look at this:

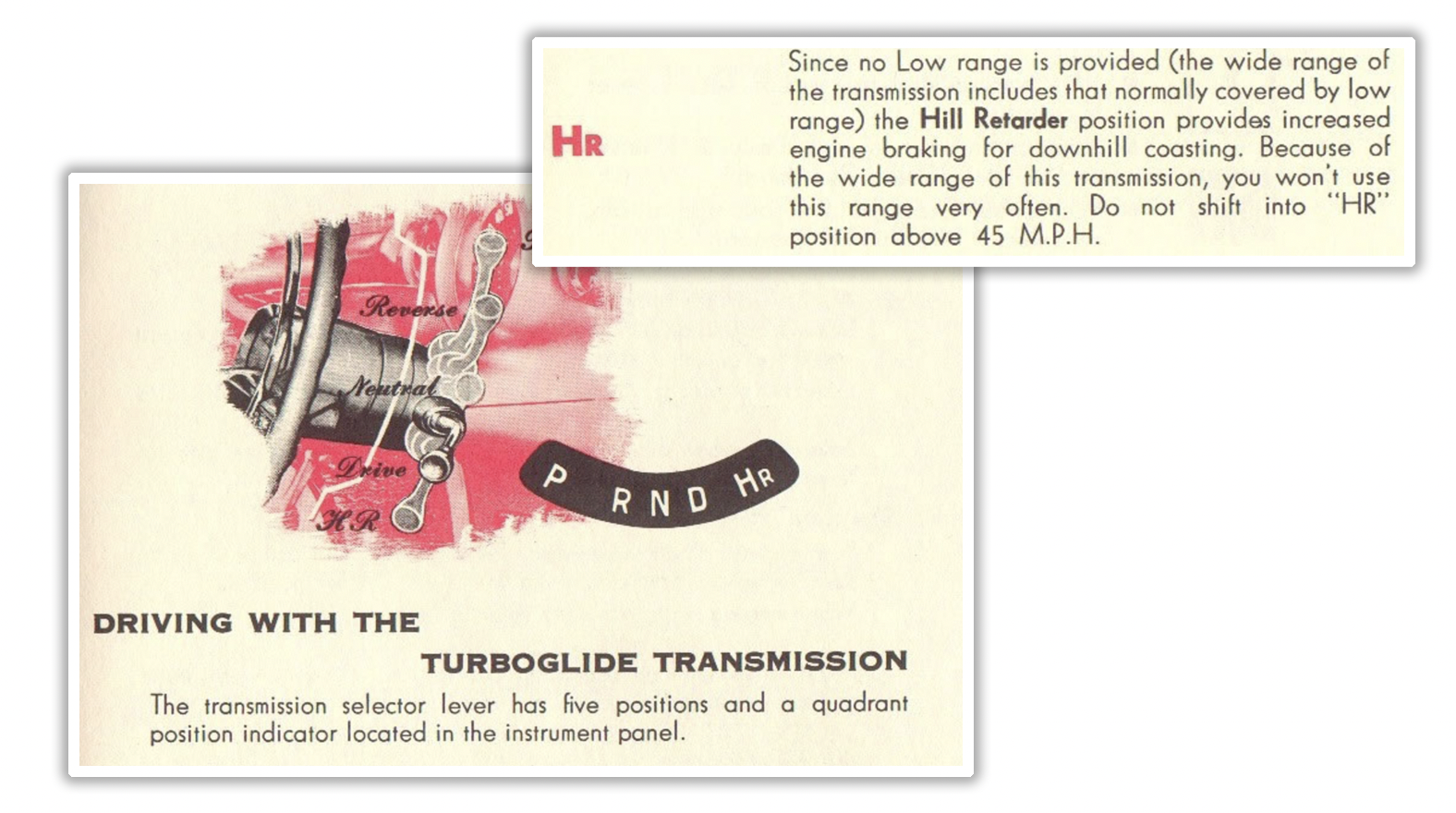

This is something I didn’t think was in use in the 1950s–essentially, this is a front/back fader system for the radio, except it’s less of a “fader” and more of an on/off switch because that’s exactly what it is. You could turn the rear speaker on or off in these Chevys, and while it wasn’t stereo (the rear speaker was just carrying the same mono signal as the one in front) it’s interesting that you could at least choose to pump the music to the back or not. Most interesting, though, I think is the realization (at least for me, and I suspect at least a few of you devastatingly attractive readers) is that GM had a continuously variable transmission (CVT) way back in the 1950s. Well, a sort-of CVT. The reason I find this surprising is that we tend to equate CVTs with modern cars, especially hybrids and very efficient cars. And while the conventional sort of belt-driven CVT (there’s also gear-based ones) was developed by the Dutch company DAF and brought to market in 1958, making it the first mass-market CVT, the GM system, called Turboglide, is pretty close to being a CVT. Maybe not exactly, but the effect of it is pretty similar. In the manual I saw, I know a Turboglide was involved because well, it said so, and this unusual gear selection:

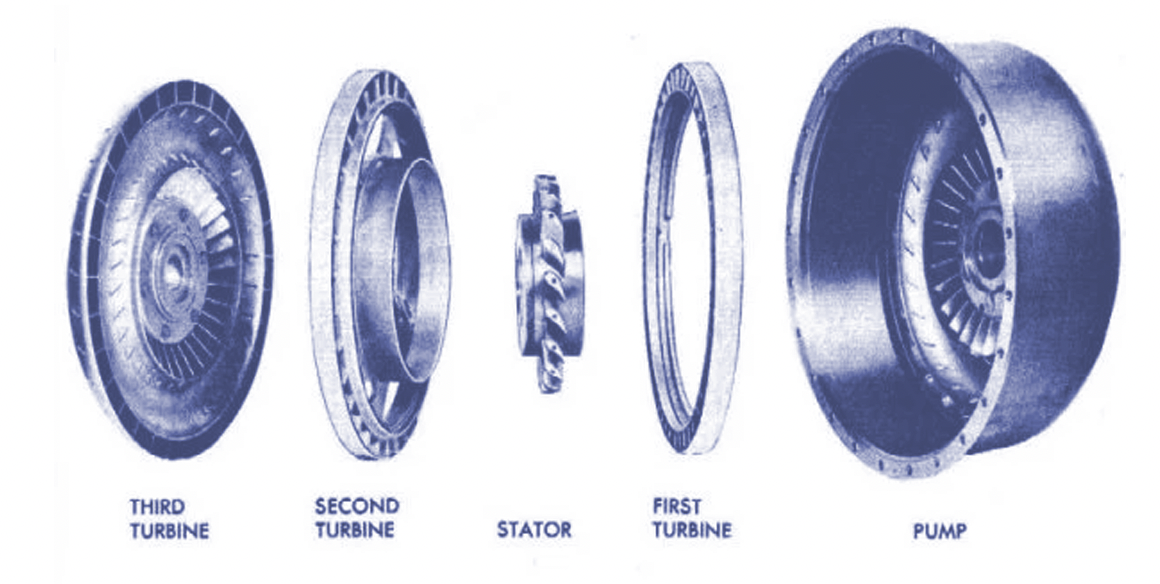

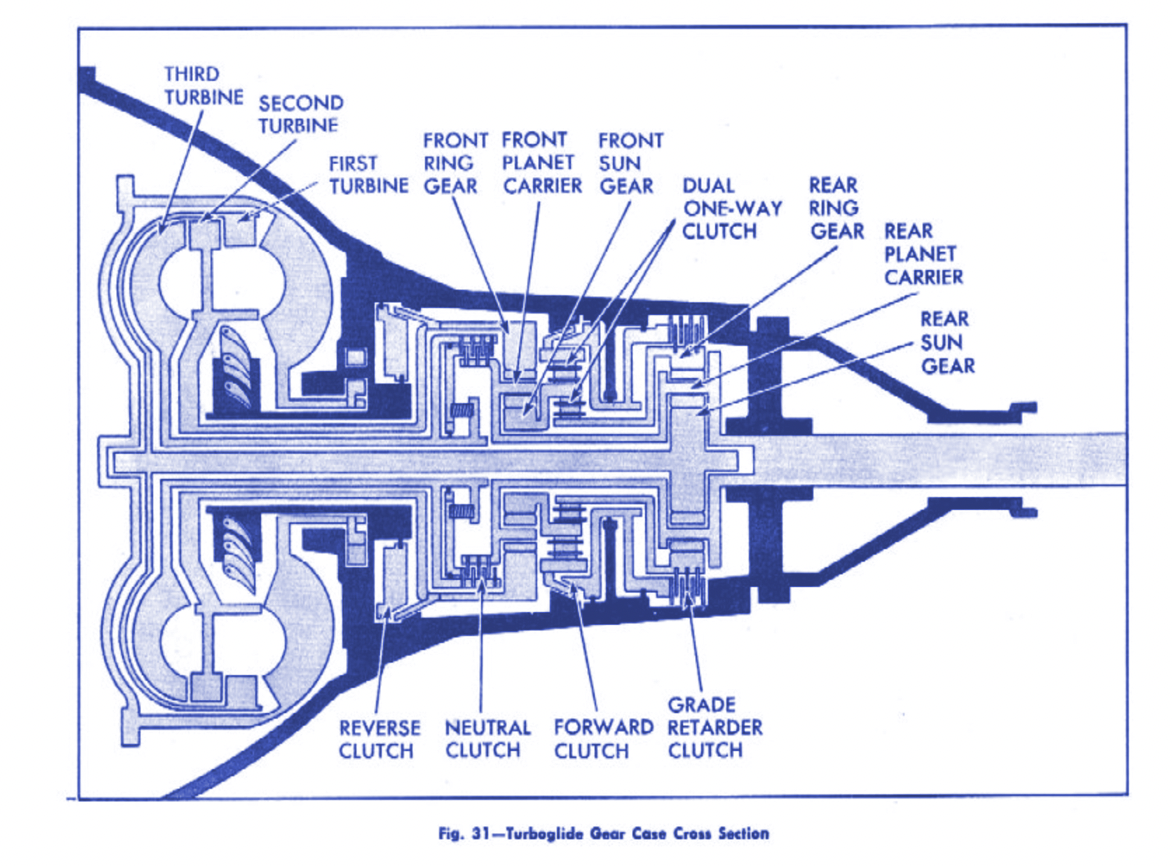

That HR range, for “Hill Retarder” has an unfortunate name not just because of the other, pejorative associations of the non-hill word there, but also because people thought it meant “High Range” which, of course, is the exact opposite of what it’s for. GM changed the name to GR for “Grade Retarder” the next year to avoid this. But let’s talk about the Turboglide for a moment here, specifically looking at it in the context of a sort-of CVT. GM’s automatic transmissions of the 1950s were generally pretty primitive, some being basic two-speed units that provided easy driving but were pretty awful for efficiency. I don’t think that was the reason for the Turboglide, as this was the era of cheap gas and a severe dearth of fucks given, but smoothness as a concept was a big deal, and the Turboglide dished that out generously. The Turboglide was a torque converter-type of automatic transmission like their previous ones, but this one had three separate turbines in the torque converter that worked concurrently to drive the car. That means the transmission wasn’t ever really shifting from one gear to another, but rather adding or removing input from the turbine couplings into the mix of ratios used to move the car. An old Chevrolet manual analogizes it with a triple-person bicycle: So, imagine that you’re starting on your bike trip, so you have all three cyclists pedaling. The one at the rear, with the smallest gear and the most torque, is doing most of the work. The high gear cyclist is barely able to do anything at this point. As you get going, the middle one is handling the most, with some input from the low and high cyclists, with low tapering off as speed increases, until it’s just middle and front, then just the front one at high speeds. The Turboglide works much the same way, sort of “blending” the three gear ratios as the car drives. The result is a lot like a CVT in that the engine revs stay pretty consistent as the car changes speed, and there’s not really perceptible gear changes. Is it a real CVT? Not really, as there are still three gear ratios, but in the way it drives and feels, it’s very CVT-like. From what I’ve been reading, Turboglides drove a bit strangely (so do many CVTs, if you ask me) and had their share of problems, eventually being discontinued in 1961. Still, this is a fascinating bit of engineering that I think tends to get overlooked, especially considering how common real CVTs are now. I’ve not found any mention how much they contribute to bruising, though. Never knew this transmission existed. I’m thinking the terms on the tire caption indicate damage to the tire. They had all sorts of weird terminology back then, “Hill-Retarder” being an awesome example. Ya get the feeling, sometimes, that they were trying to sound more advanced or superior, without being too condescending. The rear seat would basically just be for punishment. It’s also interesting that they had already moved reverse to between park and neutral, which I thought happened later. The early Powerglides and Dynaflows were P-N-D-L-R. TL, DR: If you selected that range at a stop and hit the gas, the car wouldn’t move. It would only provide engine braking. So it really wasn’t a low gear at all.