In times of national crisis Great Britain always turns to the BBC. Its charter is to “educate, inform and entertain.” Me being British and having just finished my beans on toast, let me try to explain exactly what the deal is, why designers do it and what happens between sketch and showroom.

Big Wheels

First of all, big wheels. Customers love them, because they look good. Designers love them for the same reason. Marketing departments love them because they are a profitable additional revenue stream, especially in the USA, the land of optional extras. Engineers are not always so keen on huge wheels because as the overall rolling circumference (including the tire) increases it’s harder to package. Wheels and tires have something called a ‘max in-service envelope’ that takes into account the limits of suspension travel, maximum steering angles and the expansion of the tire at high speed. If you’ve ever fitted wider (or the incorrect offset) rims to your car and experienced rubbing at full lock or going over bumps, then you’re going outside of these design limits. But modern cars are heavy. Trucks and SUVs especially have been on the Waffle House diet and as a consequence they need bigger brakes to haul their expansive girth to a stop. Which need bigger wheels to cover them. Performance SUVs have the additional wrinkle that it’s not always possible to rate a high speed tire for their weight, so they have to use low profiles or have their speed limited. If you’re lusting after the new Defender 130 one on those delicious 18” steelies, this is why you can’t have one. Those 19” alloys are the base wheel.

As cars have expanded they need larger wheels to balance out their proportions. Yeah sure back in the malaise era and before there were cars over 200” in length rolling on 15” rims with 70 profile tires. But those cars were designed around that wheel size, and had bigger wheel arch gaps because manufacturing and suspension location tolerances were much slacker in those days. More than that their shallower bodysides and higher ride height compared with today’s cars meant they could get away with smaller wheels. It’s why a lot of restomod muscle cars look terrible when they have big wide alloys stuffed into the wheel wells – their shape was never designed around that size so they look over wheeled and bottom heavy. Also most custom car builders are not trained car designers (he added, haughtily adjusting his funky glasses). It’s all about nuance and what’s appropriate for the car being designed.

So Why Do Designers Always Do It?

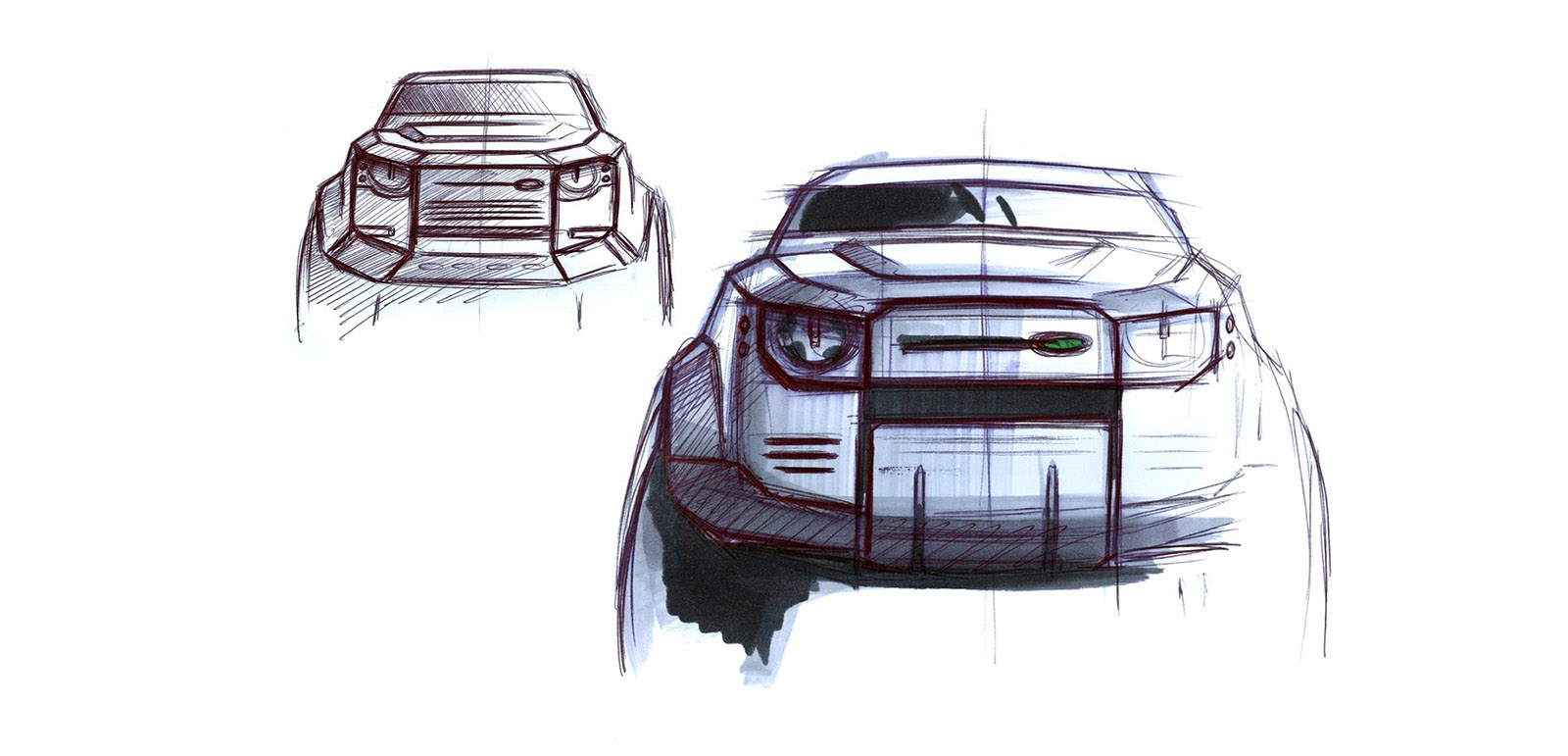

So how come designers draw such huge rims on their sketches? First of all, it’s important to understand exactly what you’re looking at. Are these preliminary development sketches from the early creative stage of a new design? Are they very fancy and detailed renders released as part of a new model release? Or are they internet content fodder from an enthusiastic amateur who has never set foot inside a design studio? Manufacturers rarely release images from the initial creative phase of the process. Sometimes they’re a bit rough and ready (my old chief designer used to love seeing the quick expressive ballpoint sketches on paper up on the board), but mainly because OEMs don’t want to show you how the sausage is made. They want to keep those ideas secret in case they want to use them in the future. If something in the development sketches appears better or resonates more with customers than the actual final car does (here’s what you could have won!), they risk a gamergate style backlash.

These images were released as part of the BMW 2 series Coupe media blitz. We should take them with a large pinch of salt, but they are indicative of early ideation sketches. You can tell the proportions are a bit off and there’s not a lot of detail. Generally, the more lush, detailed and accurate an image is, the longer it takes to do and the later in the process it comes. It’s not time efficient to spend a couple of days on a full color super accurate render that might not be selected. These show the designer getting their ideas down on paper – similar to what I have been doing in my articles. This next image is a lot more detailed and shows color, reflection and shadows. The designer has found a theme they like and are going to put it up for review. And yes, it’s stanced to hell. Why? The short answer is to make it look cool. You can think of these as caricatures – exaggerated versions of the real thing, because you want to emphasize certain parts of your design. Remember a designer is mostly working freehand – they might use an existing vehicle as an underlay to guide their linework, but this just gets them in the ballpark from a scale point of view. These are the stage my ‘final design’ images are at.

It’s All About The Drama

Getting your design picked to go forward to model stage takes a bit of salesmanship (it’s no coincidence the man who can be considered the Godfather of modern car design, Harley Earl, had a Hollywood background). It’s about the drama and the flash because the people signing the big cheques to get your design into production need to be wowed. Pulling the wheels out a bit and making them bigger helps a lot to make a striking image. If you’re lucky enough to have your theme picked to go forward to the stage (usually a full size clay model) then you’ll be expected to finesse your design onto a given package, or use an existing one if the package hasn’t been decided yet. Studio engineers will provide the data for platform hardpoints and dimensions like wheelbase and track. So the designer’s over wheeled flight of fancy gets lot more realistic in a real hurry. OEMs are not in the habit of wasting precious time and resources on a model that doesn’t somewhat represent a real car. I was once working on a sketch for a replacement car, and one of the chief designers looking over my shoulder commented “cool sketch, but you’ve over done the stance a bit!” This is why we use Photoshop because it’s a doddle to tweak things.

Finally, A Descent Back To Reality

Once a design is frozen we get into the getting it ready for production part of the design process, which usually takes about 4 years. Part of this will be evaluating different wheels styles and sizes. Full size clay models are built on an underlying armature, which allows the track to be adjusted. Initially wheel designs might just simple mock ups; full size photocopies glued onto a foam tire, but as things move along it gets a bit more sophisticated. Slave wheels of various diameters and widths can be used with different trims representing wheel designs, held in place by magnets. So you can have say, three different 20” wheel designs, and simply swap them over onto the slave wheels. These will be fitted with real tires. As production tire profiles and specifications are nailed down, things like susceptibility to curb damage and suitability for the fitment of snow chains (a legal requirement in some places) are taken into account. All the while the design team are constantly evaluating what styles work for the car. They also have to make sure the rolling circumference remains the same whether it’s on 19” or 23” wheels, because otherwise all sorts of tedious engineering things like gearing and that max in service envelope get cocked up. Designers will always endeavor to get the wheels pulled out as far as legislation allows, to avoid the car looking knock-kneed.

This final set of images reflect the final design of the 2 series coupe, but as you can see compared to the actual car they’re extremely well endowed in the wheel department. The way these renders are done is using the final production data, dropped into rendering software (usually Autodesk VRED or Unreal Engine) to get the highlights correct, and then that image is used as an underlay for the designer to Photoshop over. This allows them to get creative with the colors, lighting, background and stance while ensuring the perspective is accurate and the details correct. It’s basically impossible to create this kind of image any other way. The intention is to make them look like development renders but trust me, they’re not. They still have some of the slick designer touch but wheels aside are a lot more realistic and they’re used as part of the marketing bullshit build up when a new model is released, and form part of the image package released by media departments.

As a final note, it’s not an accident that the best looking wheels are usually only available on higher trim levels, which forces you spending more than just the cost of the wheels. Pictured above is the Range Rover Velar, on standard 19s and optional 23s. The only way to get the bigger wheel is cough up for the R Dynamic trim level, meaning instead of about $62,000 your Velar now costs $75,000. Trim levels and equipment are not decided by the design team. This is purely marketing nonsense, because in the UK you can option the big wheels on the base car for about £3500. But then again, we are a bunch of status-obsessed fashion victims. (Image credits: NetCarsShow (BMW 2 series), Miro/Medium, Mecum, Land Rover, Range Rover) Those 23″ rims would look much better proportioned as a 21″ (maybe even a 19″). The 19″ would probably look better as a 21″ or a 23″, but weight might be a problem/deletrious effect scaling them up (not sure if the cross-section on that wheel design is solid, given the marque). Instead a big honking SUV gets long thin spindly wheels or particularly short and stubbly wheels, even though neither fit the form of the end product very well. In Europe it a lot of it came from those late eighties/early nineties homologation specials. I got it now, and won’t be kvetching further on wheel size in your drawings. Is what it is. It’s all about proportion and balance. You can go too far absolutely, but OEMs generally don’t. The aftermarket is another matter entirely. I have several classic Minis, some on 10’s, some on 13’s and both look correct. The 13’s give it a little more of the bulldog look as they require arches – in my case fairly large ones were fitted from the factory (my car was built in Seneffe for the German/Euro market so they are different than Sport Paks on English built cars) but the 10’s with their 70 series tires definitely drive better than the ones on the 13’s with 50 series rubber – those tend to tramline and lower the fuel mileage and top speed too! So, like most people I’ll bet – I like the looks of the 13’s but prefer the drivability of the 10’s. Larger brakes on the later cars required the move to larger wheels – 12’s in most cases and the 13’s were only offered as a style or look, they weren’t needed to clear the brakes. But the more to 13’s required the big Sport Pak arches and stops on the steering rack so the wheels wouldn’t rub on turns. The difference in weight between these is huge, almost twice as heavy when going to the 13’s, which of course affects spring and shock rates……also contributing to the change in ride/drive quality. On new cars (we have a late model Audi Allroad) I can barely lift the 18’s that are used, let alone the 20-22’s used on American SUVs! I would definitely like to see them go back to a smaller, lighter wheel/tire combos! My 78 Audi 5000 looked and drove great on its 14″ wheels, but it also weighed about 1300lbs less than my current car, and that one is on the lighter side of what’s being sold these days. Weight begets weight. My Range Rover has 20”s. I hate to try and lift one of those. But punctures are a bit of a thing of the past these days luckily.